Festivals – Celebrating the coming together of earthly and cosmic forces

Festivals are a celebration of the seasons of the year and connect us to the world around us. They fall in an annual rhythm that can be strengthening to the physical body of the young child.

Read MoreWhy a class play in Waldorf Schools?

For almost every grade in most Waldorf schools, there is a class play. This is an exciting event and means a great deal to everyone: the teachers, the students, the parents, the extended families of students.

Read MoreThe Journey of Advent

In the Southern Hemisphere, the festival of Advent and Christmastide takes place in the heart of Summer, when nature has fully unfolded, and everything is in abundance. The school is teeming with flowers, greenery and fruits, and the days grow steadily longer.

Read MoreSports at a Waldorf School

Sport is an essential part of the Waldorf curriculum. Yet the approach to sport is fundamentally different from the way it is taught at conventional schools.

Read MoreMontessori and Steiner: A pattern of reverse symmetries

Both paths are brilliant, full of compassion, and honouring of the child. Each path has the same obligation.

Read MoreNew life, new hope – The message of Easter

What makes Easter an exceptionally unique festival in our modern world, is that it is never a fixed date in our calendar year. Easter Sunday is always the first Sunday after the full moon following the Autumn equinox.

Read MoreThe Seven Lively Arts

The Seven Lively Arts evolved from the concept of the Seven Liberal Arts of ancient times; these were the key subjects one would master to become a scholar.

Read MoreThe Light of St John’s

The festival of St. John takes place in the heart of winter in the Southern Hemisphere, while the earth appears to be in a deep slumber.

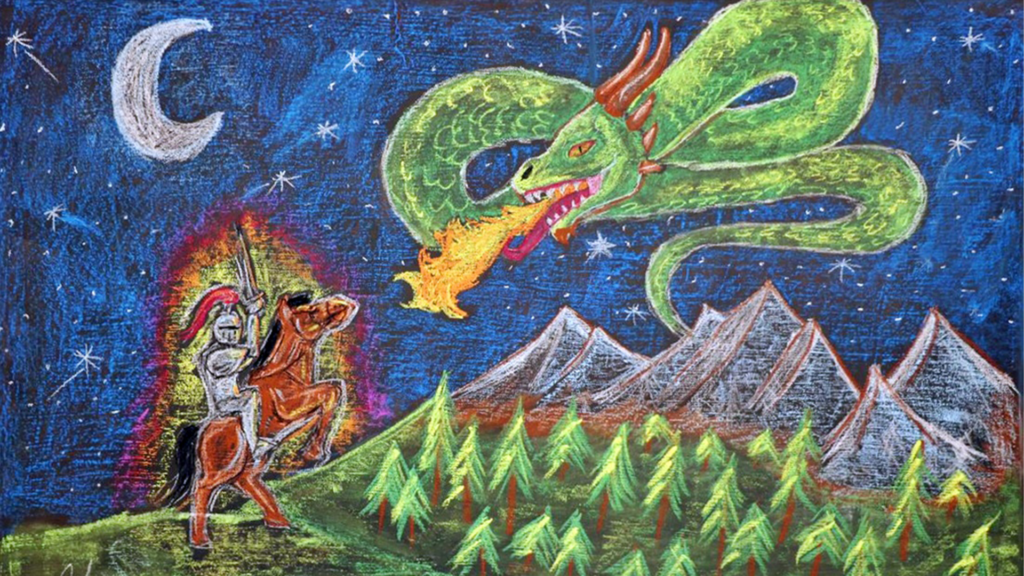

Read MoreThe message of Michaelmas

In the Southern Hemisphere, the festival of Michaelmas takes place in the heart of Spring. The Earth is awakening from its slumber, releasing an abundance of renewed energy and beauty.

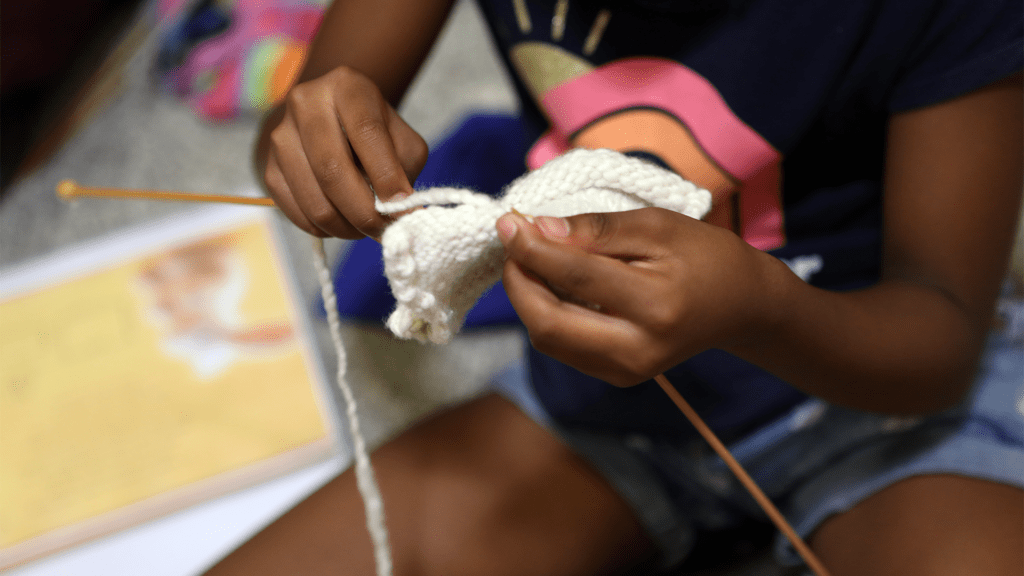

Read MoreHandwork in the Waldorf Curriculum

There are many reasons given for the importance of handwork as part of the Waldorf curriculum. Among them is that handwork gives the human being practical skills in many different directions; its purpose is to give a person an all-round understanding of life.

Read More